I spoke at a conference a few years ago where screens all over the venue showed “meters” for how large the crowd was in each speaker’s room during sessions. There were bars next to the speakers’ headshots, showing the room’s level of remaining capacity. It was said to be for the purpose of helping people know if a talk was “full,” but the fact that people crowded into certain ones anyway showed it didn’t matter much. Instead, it became a chess piece. I was asked more than once about my own talk, “how full was your meter?”

Heading up an apostolate and having any sort of public aspect to my work exposes me to many iterations of that question: “how full was your meter?” “What is your nonprofit’s reach?” “How many hits does your website have?” “How many subscribers?” To choose ministry or apostolic work seems to connote choosing an online “presence” of increasing reach, with the size of the audience dictating the size of the mission’s efficacy. Being visible, and being visible online, are “fundamental” to ministry success. In the first couple of years after founding, I was in a grant competition that also served as a pseudo-leadership intensive—a masterclass of sorts. In a webinar about social media and marketing, I asked what organizations, such as ours, that chose not to be on social media could do to still conduct outreach. The answer from the expert?

“Your apostolate will not survive without use of the Meta suite.”

Though we’ve since proven her wrong, I wonder about the implications of her warning regularly. In the post-digital revolution, post-Vatican II America, the online world is not just seen as a place for laity and clergy alike to evangelize, it is now seen as the only place to evangelize—and that ministry is turning a profit. The online ministry world is tied to, and often dictates, what happens in the real one. True apostolic work, apart from approved metrics such as social media presence and a thriving email subscriber list, what have you—does not seem to exist. Or if it does, it’s not recognized. Ministry success is measured by new standards—standards that didn’t exist before, and standards that I think might be changing the nature of evangelization itself. We might gain a following, but we might lose the heart of the Gospel in the process.

Evangelization and Capitalism

Part of the uniqueness of the apostolic landscape in which we find ourselves is its consistent fusion with a capitalist society. As I was taught ad nauseam in high school, “capitalism is an economic system AND it’s a cultural system” (thanks, CrashCourse). Escaping that cultural system is near impossible, even if your work should transcend such systems in the first place.

Nonprofits, in a way, are supposed to supply protections against motivations that a capitalist system inherently brings—the very fact of letting go of standardized “profit” being the first. The main “capital” in a nonprofit organization cannot be made by program or product revenue, as anyone who painstakingly fills out 990 forms annually knows. Instead, the bulk of revenue comes from donors, grants, or other forms of benefactory funding. There are also no shareholders—a major piece of the capitalist market. If I walk away from the organization, despite founding it, I walk away with empty hands. Even now, I make nothing but a salary voted on by a board of directors, subject to their change and approval.

In an incredibly simplified summary, nonprofits are essentially supposed to “run” primarily on donor funding to accomplish their work. Its beneficiaries are not a client or customer, and employees are not beholden to sell a product or service. There can be charges or fees associated with programming, but again, they are not the main source of revenue, and rarely even cover the cost of programming itself. Beneficiaries come with a need that the organization seeks to fulfill—similar to a for-profit company, but with the important distinction that the fulfilling of the need is not the main source of revenue. Again, this is heavily simplified, but it’s key.1

From a personal perspective, it blows that I have to fundraise to do our work. I wish I could just…do it, and not have to spend time in development. But in order to keep our figurative doors open, we have to have some level of funding—and it’s a major part of my job to find it. In this aspect of my responsibilities, though, I feel the protection of being a non-profit. Knowing I am spending money generously given by people who receive nothing from us for their gift encourages me to be prudent where I wouldn’t be. It imbues a spirit of gratitude in our operations. And finally, it reminds me that the day I feel I would no longer minister in this space, whether or not I made a paycheck (I didn’t, for a while), is the day I should walk away. That’s the signal that the zeal, the calling, is gone. Funding can come in a flood, and it also can dry up—if I’m in it for the money, I chose the wrong industry. Funding, essentially, can go up and down, but the mission can remain the same whether under surplus or strain.

A subtle, but fundamental change occurs in ministry in a capitalist society when beneficiaries become a client or customer, under the guise of still being a beneficiary. This happens often in for-profit businesses in faith-based spaces and topics, a plethora of which I could list here, but I can imagine you don’t need my help thinking of them. In these businesses, whether it’s a one-man show or a massive corporation, people’s spiritual needs are not fulfilled primarily through the generosity of an outside donor, funding a ministry’s service, that then serves their need with a form of protection against self-interest. Instead, their spiritual needs are the target of marketing of a product, the purchase of which directly profits the business—employees and shareholders alike.

I am not saying the particular works of all of these companies are necessarily wrong, nor am I saying people’s needs aren’t actually met by their products at times (though I have plenty of thoughts in that arena). What cannot be denied, though, is that the definition of ministry is changing—faith is a market, a brand, a product, even, and “ministry” is now a means for profit, when by its nature, it was never meant to be.

Dictatorship of Growth

“Ministry” in a for-profit, capitalist system is thereby tied to the mission of growth, in which success is measured by increase, not necessarily by efficacy. This mission of growth, in effect, replaces the mission of fulfilling the original need the company set out to. Again, the change is subtle, and the sweet little American mind may think “what’s wrong with that?”, but there’s a lot wrong with that.

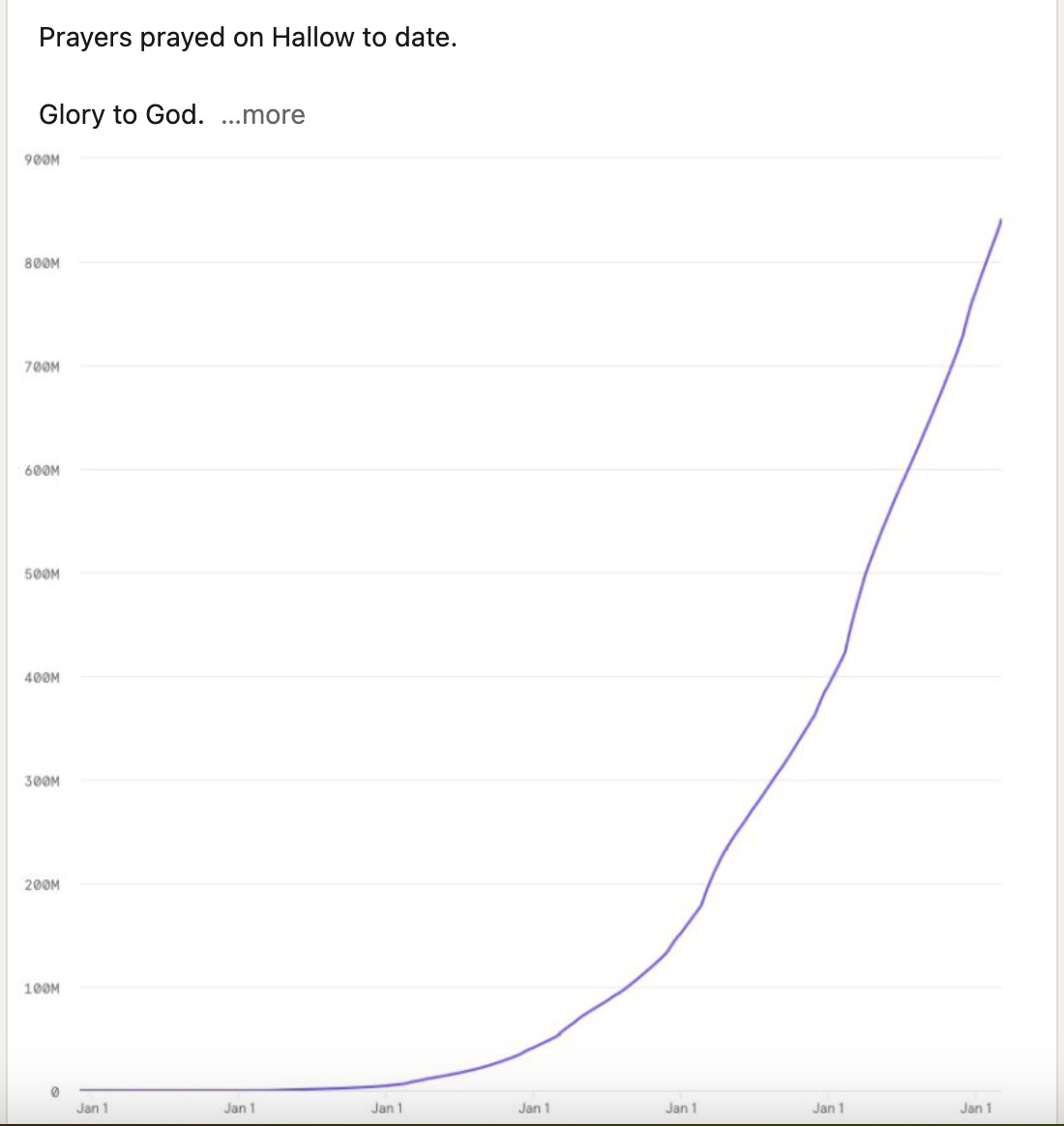

When growth becomes the mission, as dictated by profit, the numbers become the metric of success instead of the actual fulfilling of need. As an example, the CEO of the prayer app Hallow posted this graph a few months ago.

“Prayers prayed” is a pretty vague descriptor. Again, this is not a critique of Hallow (though…tempting). Seeing this should make us ask how something as transcendent as prayer is possibly measurable, and if we don’t ask that question, we should find it strange that we don’t. This graph is probably solely created from assessing engagement on the app—how many times people tapped, not how many times people actually prayed (and by its nature implies a delegitimization of prayers not prayed with the app). The point of this is that it betrays the problem with the for-profit, ministry fusion—people become a metric in the mission of growth, rather than unique souls to be served. Graphs like this are impressive on the surface, but growth is not the measure of success in a mission; at least not an other-worldly one. Increase in numbers does not mean a mission has been fulfilled, unless, I’d argue, numbers are actually your mission. That’s an attitude adopted from the digital world. Hallow may certainly have helped some of those people pray—but for many people included in that ever-climbing graph, I’d venture to say it was an obstacle to their growth in prayer. Again, song for another time.

“Reach” or “numbers” as mission (“how full was your meter?”) would be a foreign concept to St. Isaac Jogues, or Dorothy Day, or St. Teresa of Calcutta, or any of the great “missionary” saints we revere. By way of analogy, Neil Postman makes a similar case in Technopoly about how the technology of the grading system would be foreign to the great thinkers and scholars of other generations:

“If a number can be given to a quality of a thought, then a number can be given to the qualities of mercy, love, hate, beauty, creativity, intelligence, even sanity itself…To say that someone should be doing better work because has an IQ of 134, or that someone is a 7.2 on a sensitivity scale, or that this man’s essay on the rise of capitalism is an A- and that man’s is a C+ would have sounded like gibberish to Galileo or Shakespeare or Thomas Jefferson. If it makes sense to us, that is because our minds have been conditioned by the technology of numbers so that we see the world differently than they did. Our understanding of what is real is different. Which is another way of saying that embedded in every tool is an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing rather than another, to value one thing over another, to amplify one sense or skill or attitude more loudly than the other.”2

This is what I mean by stating that the great missionary saints would likely be baffled by a graph of “prayers prayed” on an app, or by a fundraising newsletter boasting of website hits, or new initiatives being equated with ministry fulfillment: to say this about apostolic work is to have a different understanding of apostolic work, entirely. To measure the “effect” or “reach” of apostolic work is to subject its meaning to a statistical technology, one with particularly digital implications. “Reach” and “engagement” are terms largely used to describe online activity.

Any of those missionary saints would have done their work for one soul. Many of them said such. We, on the other hand, probably cannot say the same when profit and digital technology are involved. Souls are not just souls anymore—they now have market value. Despite our assertions otherwise, this colors what we do.

Creating Dependency

At the beginning of my journey of founding Magdala, I was agonizing over small details of scale and efficacy when someone wise told me: “Rachael, everything you build will die.” His point was simple, but grounding: this apostolate will end. It could last a decade, or it could end before it even starts. Regardless, it will end—and perhaps that should inform its operations.

In my mind, the apostolates I trust the most are the ones that work toward their own destruction—not by mismanagement, but by elimination of the need they set out to fill. Granted, while some needs can never fully be filled earthside, we should long, and aim for, a completed mission. If I am serving women struggling with sexual addiction and compulsion, I should genuinely hope that one day my organization does not have to do so—whether because another place comes along that serves this need more fully, or because the issue disappears altogether. This applies to each individual person as much as it does the issue at large.

The phrase memento mori, “remember your death,” carries significance in the Catholic tradition. We are meant to always keep at the forefront of our consciousness that one day, we will meet our Creator, and we do not know when that day will come. With this in mind, we can aim to detach from our daily work and callings, knowing that in the end, we must return to our origin. Ministry, in my mind, should also remember its death. “He must increase, we must decrease.” Just as John the Baptist turned his personal disciples toward Christ without hesitation when He revealed Himself, so we must not seek to create dependency on our apostolate, let alone ourselves, in those we serve. Whether or not we actively seek our own decrease—again, some needs have more longevity than others—we at least should not be alarmed and resistant when it comes.

The modern ministry space, colored by profit and under the rule of digital engagement, is naturally motivated by increase—numbers being the metric of effectiveness is only one showcase. While that increase may be justified by saying more people are “receiving the Gospel” or some other iteration, underneath these justifications are still the dictates of growth trajectory, which swallows souls on its way up. For-profit companies, by their nature, do not benefit from losing customers—quite the opposite. By their nature, they cannot work for their own elimination. Instead, they are motivated to retain customers—again, often under the guise of beneficiaries—by creating a dependency, an ongoing “relationship” that, in turn, creates more profit. Growth in a capitalist, for-profit model requires companies to either gain new customers, or constantly demand more from their existing ones. This is behind the constant need for these groups to create something “new”: new programming, new products, new challenges, new content, new podcasts. “Newness” makes their customer base stick around, afraid of missing out.

As Postman says, to use a technology—whether the ubiquitous technologies of numbers and statistics or the complex landscape of social media—is to subject ourselves to its ideological bias, to emphasize or prioritize one thing over another. “Ministry” subjected to either of these technologies is not primarily service, it is commerce.

Influence is Not Evangelization

I thought about wrapping up this piece with the above points, but one final element of modern ministry and evangelization, subject to capitalism and technology’s effects, is a glaring part of this to me: that of Catholic “celebrity.” Fame and recognition dictate the ministry space more than it ever has before, controlling much of what information we consume and trust, whether or not we realize it.

Celebrity, much like Postman’s assessment of technology, inherently colors what it touches. As Katelyn Beaty says in her book Celebrities for Jesus:

“Celebrity, in the final analysis, is a worldly form of power and evaluation of human worth. It is not a spiritually neutral tool that can be picked up and put down, even for godly projects. The moment celebrity is adopted and adapted for otherwise noble purposes - sharing the good news and inviting others into rich kingdom life - it changes the project. And it changes us.” 3

Celebrity, much like profit or digital technology, naturally brings along with it elements of self-interest that are impossible to extract—often, elements of self-interest that are incompatible with true service.

It’s not the fault of modern evangelists that in the past, many missions meant almost certain death—such as in the case of the Jesuit martyrs, or the Apostles themselves—and that now, the landscape has changed. But now, those we deem true “evangelists” often get book deals and conference keynotes (see also: profit) in conjunction with their mission.4 Again, this doesn’t make their work necessarily wrong, nor ineffective. But it does change the nature of what we’re accepting as “evangelization” or “ministry.”

Social media influencers, for their part, take the primacy of celebrity to another level. For influencers, engagement is directly correlated with profit, and the faith is often used as a prop to sell skincare, makeup, household products, or other unrelated items (for pieces on engagement farming and grifting by faith-based influencers, see

and ’s pieces on the topic). Even without sponsored content, faith is the product. These accounts can deem themselves “ministry,” but ministry serves their brand, not the other way around. It’s worth asking if their follower count stayed at a normal level and never increased whether or not they’d still spend time “ministering.” What we become attached to when any celebrities are the voices we turn to are personas, not people. Real ministry cannot happen without encounter, and encounter must be person-to-person, not persona-to-person.Again—I say it repeatedly, because there’s a risk of the core problem being lost here—just because individual people or companies make money, does not make them bad. I am not saying profit or reach or engagement are evil, or that people trying to gain any of these are evil. I’m not saying capitalism is evil (but deeply imperfect and…loaded? Hell yes). What I am saying is that these aspects of modern ministry, by nature of being present, change what we understand to be “ministry,” and I think for the worse. There’s a reason why both fame and money are among Thomas Aquinas’ “Four Idols,” and I don’t trust anyone who thinks they are above being tempted and changed by their presence. What I simply cannot stand is when an idol seems alive, well, and thriving, still under the guise of a term that should mean humility, sacrifice, and hiddenness.

Influence and virality are not the same as evangelization, especially when you are motivated to keep engagement up because it turns a profit or secures opportunities for you. It’s also worth remembering that before virality was a term associated with online success, it was only applied to disease…and it was negative. Virality does not mean goodness, beauty, or truth. Can it? Sure. But we automatically mistake popularity for orthodoxy and follower count for authority, and that’s to our detriment. If we accept superficial qualifications for what we receive spiritually, we cannot expect much to work its way to our depths and last.

Because of this, the Catholic “celebrities,” or thought leaders, or however you want to describe them that I actually trust are the ones that don’t actively seek to promote a personal following. They do their work, they do it well, and they don’t manipulate people’s time and attention by using their authority to sell products for kickback. Those who actively seek increased following, especially under the guise of “ministry,” are the ones I avoid. Though there’s a common claim that it’s not their following, it’s God’s, that claim necessitates a belief that following them inherently means following God—to me, that gets into even sketchier territory.

Roman roads

Part of the glow of the primarily online new evangelization market is the appeal that it’s working. So many more people are praying, evangelizing, believing because of all these things, right? While again, products and companies in the for-profit world have certainly benefited people at times, is it that much better than what we had before?

I consistently hear the analogy that St. Paul used Roman roads to spread the Gospel, so we need to use the secular tools available to us to evangelize and minister. This argument is most often applied to digital technologies, and social media specifically—and now into the ever-expanding behemoth of artificial intelligence. There’s an imperative that if we abandon the medium, it will only be used for evil, and so we are obligated to use it “for the good.” But, to quote Marshall McLuhan’s famous aphorism, “The medium is the message.” While Roman roads didn’t change the nature and effectiveness of the Gospel, social media does. Heidegger defended that technology is not neutral, not malleable according to human agency or activity. It brings with it, like Postman says, an ideology. That doesn’t mean truth cannot get through in the online world—it’s just worth asking, truth contorted by what, with what mixed in?

Heidegger also emphatically said that we are never more duped by technology’s ideology than when we believe we’re somehow above it—when we believe that it is subject to our design, rather than the other way around.

“Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral; for this conception of it, to which today we particularly pay homage, makes us utterly blind to the essence of technology.”5

While our numbers may look impressive, I’d say we’re also losing much. Our pews are not full, and modern faith can feel shallow, distracted, often kitschy. A triumphalism that forgets the heartbreak of scandal or the vastness of suffering—not to mention the darkness, the deep poverty within each one of us—dominates the landscape. Divisiveness pervades our dialogue. We crank out content, but we haven’t the faintest idea how to contemplate. In many ways, though our Church is incredibly active online, that also has rendered us, in many ways, a Church content to exist in “the shallows,” when the most unfathomable of depths is available to us.6

So…what now?

The best evangelist I know is a man named Marc Lenzini. He is brilliant, hilarious, and the Gospel pours through him—both in word and in deed. He taught moral theology my junior year of high school, and by the time he retired, he had taught there for almost 30 years. His stories were electric, his handwriting was terrible. And he changed my life.

In fact, many a Catholic raised in the greater Denver, Colorado area owe their faith to him. There’s stories of atheist students experiencing radical conversions sitting in desks in his classroom. One football player famously stood up in the middle of class, after fighting him all year, and his torso was so large that his desk was lodged around him. “It’s all true,” he said. “Everything you’ve been saying…it’s true.” Supposedly, he’s a priest now, but that could also be Bishop Machebeuf High School lore.

Mr. Lenzini was the first to set the fire of studying the faith in my heart. I had been raised in a devout Catholic home, but sitting in his classroom that whole year, I desired not just to make the faith my own—but to dedicate my career to it, my life to it. He made me want to pass it on. He had a mastery of truth and charity in whatever he was speaking about—whether it was marriage and family, drugs, or LGBTQ+ needs in the Church. He just…lived the truth, and was in love with it.

I met with him my senior year to talk about majoring in theology in college, to ask him whether or not he thought it was a good idea. It was a massive pivot from what I had thought previously, but I wanted to teach, like him, I said.

He met with me in his classroom, though I wasn’t a student there anymore—it was 7 am, and he brought me donuts. We talked for a long time about my dreams, what I wanted.

At one point, he looked away. I remember he looked tired. “If you give your life to the truth, people will hate you,” he said. “But it’s worth it. And what they think…it just doesn’t matter.”

I’m thinking of that now, as I’m sitting here milling around terms like capitalism, profit, reach, engagement, ministry. At the bottom of all of it, Mr. Lenzini got it—he saw through the bullshit. He did not give his life to the truth to be loved, to make money, or to gain accolades. He probably made a pretty shitty salary, to be honest. In fact, he did it knowing he’d be overlooked, even hated, and would get shitty pay. He never sought an audience beyond the classroom, and his career in that classroom ended a bit tragically—but that’s another story. To me, he is his own version of Isaac Jogues or Teresa of Calcutta or Dorothy Day—he did the work assigned to him, quietly lived and died for it, and he will reap the rewards for eternity.

But still, he changed my life. Mine is one among many. And he changed it without making any profit off of me, without making anything off of my time, without ever boasting of numbers or conversions—he changed my life, and he probably doesn’t even know. I can confidently say I would not have chosen the path I did, were it not for him. He would be repulsed by the behavior that is so common in supposed apostolic work, and I think he’s right, as he was about so many things. I’m thinking not only of him, but of the church employees I had the privilege of walking with in my first job after grad school, the parish priest who loves his flock and doesn’t post his homilies online, of the beloved Disciple letting go of his own name because it doesn’t matter anymore. He has someone else’s Name to lead people to. That’s ministry. That’s evangelization. The truth is worth loving, and worth being hated for.

Maybe we are helped by certain faith-based products, or our faith is changed for the better by a Catholic celeb. But again, it’s worth asking ourselves: in exchange for this, what are we losing? Again, when we accept the Gospel with dashes, threads, or even heaps of self-interest or superficiality, what Gospel are we accepting? And what Gospel will we then be compelled to share? Perhaps it’s idealistic of me, but I don’t want a Gospel watered down by profit, desire for following, by online rules and ideologies—an eternal truth measured by worldly metrics. I want the real thing, and despite my immense imperfections, I want to give the real thing. Maybe it’ll be immensely hard to find, in a world dominated by digital technology’s ethos. But it’s out there.

I don’t think it’s too late to change this dilution of ministry or evangelization’s nature. We can recognize the system we’re in, and aim to be as unaffected by it as possible—while being honest about the times when we are. We can turn to the people in our life who deserve our time and attention, who aren’t asking for it—we can receive their wisdom, put the phone down, look away. We can let Catholic celebrities be just people, who can be right or wrong. We can stop accepting consumerism under the guise of service, and we can examine our own intentions when sharing the Gospel. We can reclaim a Church of discipleship rooted in contemplation—where many of us, rooted in friendship with Him, are content with whom He sends us in our proximity, without counting heads.

“How full was your meter?” people may ask. I hope, one day, we can all answer with the same shrug of Mr. Lenzini:

“I don’t know. It just doesn’t matter.”

Not saying nonprofits can’t be icky and are protected from being so by dint of being a nonprofit. Sadly, that is too often not the case. Again, offering a simple summary for the sake of argument here.

Neil Postman, Technopoly. 13.

Katelyn Beaty, Celebrities for Jesus: How Personas, Platforms, and Profits Are Hurting the Church.

Not to bring this back around to Hallow, but credit where credit is due: CEO Alex Jones also has publicly stated that profit from his shares in the company are given back to the Church.

Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology.

Borrowing this term from Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows.

This is so good, Rachael. You've articulated something that has been bothering me for quite a while. Thanks for having the courage to write this!

Yes to all. I have largely stepped back from my own platform because I felt drowned by the faith as product zeitgeist. It was drowning. It is drowning.